(ANGLICAN)

ALBERT STREET, SEBASTOPOL, BALLARAT

Roof repairs beyond the parish resources.

Well, at least it’s not going to be Heavenly Pizzas or an “Arts Hub”.

Sebastopol Anglican church, Holy Trinity, on the southern fringe of Ballarat, has been sold to a Sikh group, who will use it as a centre for their community. From Anglicanism to Sikhism in a provincial city’s suburbs is a fairly good illustration of our nation’s current demographics.

Holy Trinity wasn’t put up for sale for the usual reason – that nobody much went to it. It had an active parish life, a reasonable-sized congregation and even – a rarity these days – some younger families and their children. The problem was the roof, not of Holy Trinity itself but of the 1850s stuccoed-brick former church beside it, now used as a parish hall. This had been damaged in a storm and needed expensive repairs that were beyond the resources of the parish and, presumably, the insurance payout.

The following information has been contributed by local historian Dr Juliette Peers.

“The major problem was the roof repairs in the 1850s original church, which had become unusable due to storm damage. Equally the historic nature of the building was a problem, bringing with it the difficulty and expense of sourcing roof slating to replace the 1930s and 1950s asbestos roofing, the latter substance demanding again more specialist treatment which is equally expensive although not so visually glamorous as historic restoration. All of which had put repairs beyond the funding that a congregation and sausage sizzles could reach. These complex problems were the tipping point for the Anglican diocese in its decision to sell the site despite the relative health of the congregation.

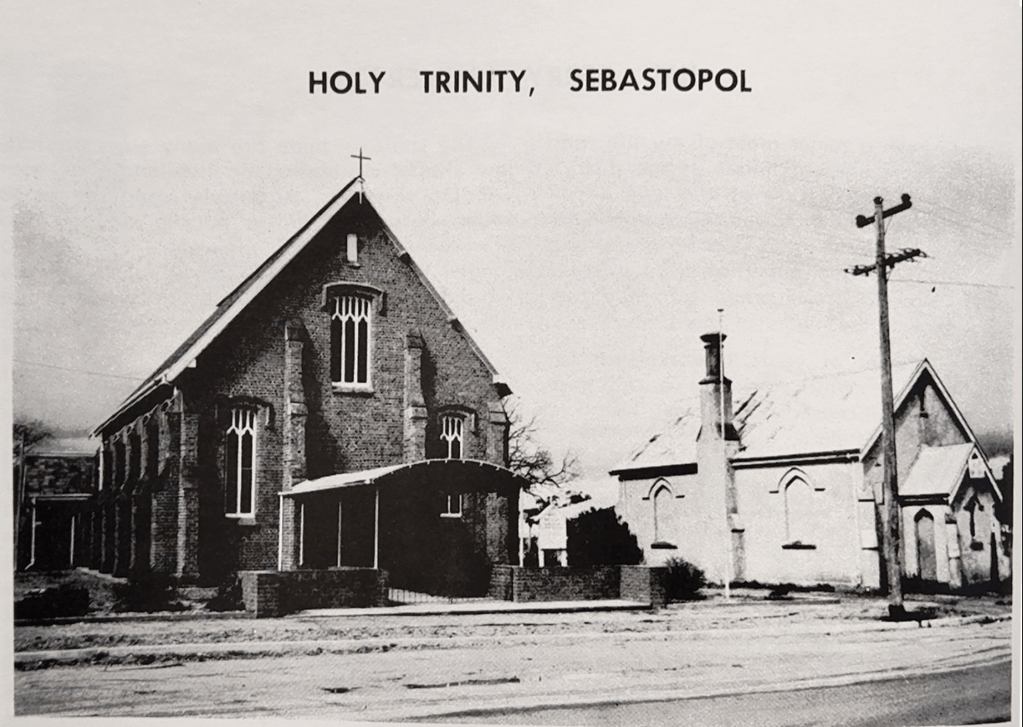

“The Holy Trinity church complex was noticeably attractive with its early church of the 1850s and a later moderately grand Church – very swish for a working class mining community – in the rather strong and bright orangey red brick that characterises much 1850-1890 brick construction in Ballarat and has a vibrant tone not seen in Melbourne brick and clays. The church was not very “high” (Ballarat is a largely Anglo-Catholic diocese) but has colourful windows and woodwork of a high quality. Behind it is a much later and rather utilitarian timber hall and there’s little bit of cottage-garden planting.

“So much community love and energy in there.”

The old 1850s church was soon too small for the parish and a larger church was commissioned and opened on 26 January 1868. It consists of nave, chancel and lateral vestry, built in two stages. The architect was Henry Richards Caselli (1816-1885), who emigrated to Australia from Cornwall in 1853. He worked first in Geelong and then “attracted by news of gold” (Federation University biography), “travelled to Ballarat where he witnessed the Eureka riots.” After a time prospecting he resumed work as an architect and designed many public buildings in Ballarat, including at least five churches.

Holy Trinity is oriented east-west and has Caselli’s typical low-arched windows, an interpretation of English Perpendicular Gothic, on the front facade and along the nave. The handsome east window is English Decorated in inspiration. There is an ironwork bell-tower beside the vestry. The 1850s former church has a fireplace and chimney, often seen in the vestries of nineteenth-century churches but most unusual in a nave.

The front portion of the new Holy Trinity was opened for worship by Bishop Perry (of Melbourne) on 26 January 1868, the chancel end being closed off with wood to allow for future extension. In three years this building too was too small, and it was extended to its present size and re-opened in March 1870. Since then it has remained unaltered, apart from a hideous 1960s covered walkway at the front, which perhaps the Sikhs will do away with.

One wonders, though, why the damaged hall could not simply have been abandoned with its roof unrepaired and the church retained.